2026 edition

The garden

star of the show

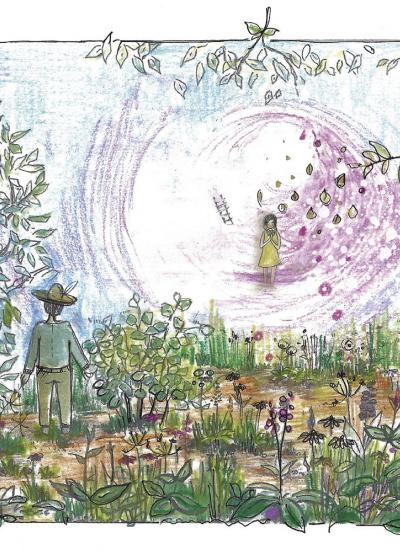

Gardens are places of memories, seasonality, presentation and emotion. Both real and symbolic, they provide a stage for taming, tidying and cultivating nature – without ever entirely controlling it. For the great art of time, spectacle and storytelling that is cinema, gardens serve as a partner that delivers a level of aesthetics and poetics rarely found elsewhere. The theme of the upcoming Chaumont-sur-Loire International Garden Festival, The garden star of the show, encourages visitors to explore the formal, narrative and symbolic connections between these two arts.

Gardens have been used as film sets ever since cinema first began. Filming in these sorts of settings is never neutral. It is inherently emotionally charged, harbouring incredible theatrical potential. From bucolic scenes to moments of terror, from childhood locales to fantasy lands, gardens can be a refuge or a trap, a utopia or an initiation, a paradise or an allegory.

What cinema shares with the art of the garden is that same focus on perspectives, lines and flow. Both organise and structure space to steer the viewer’s gaze. Gardens are staged with the intention of being roamed, and sequences of film shots with the intention of being read. In both cases, movement creates an implicit narrative. Gardens can thus be conceived as a cinematographic tool, a moving scene where light, rhythm and matter all coherently interlink in time.

A number of filmmakers have turned gardens into far more than merely a set: Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970), Agnieszka Holland’s The Secret Garden (1993) and Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro (1988), just to name a few.

The concept of time is another good reason for drawing parallels between cinema and the art of the garden. Gardens grow and transform, following the seasons and at the mercy of the elements. Cinema, meanwhile, plays around with multiple dimensions of time, expanding it, condensing it, fragmenting it and rewinding it! Filming in a garden is thus an act of adding a sense of moving, evolving temporality to an image, of capturing the slow development of the living world. Derek Jarman made a garden the central theme in The Garden (1990), as did Peter Greenaway in The Draughtman’s Contract (1982).

Beyond evoking all these films, Making a Scene? The Garden on Camera encourages visitors to consider gardens as a narrative tool that links sequences (parterres, paths, flower beds, groves…), creates transitions (fences, thresholds, doorways) and regulates intensity (light and shade, empty and full spaces). Landscape gardeners, much like filmmakers, create a sequential, polyphonic oeuvre in which visitors become active audience members. Gilles Clément refers to gardens as ‘writing in motion’, as ‘living screenplays’, while Bernard Lassus sees landscapes unfolding like a film or a strip of images.

La lanterne des profondeurs

Avatar

Paysage-montage

Drôle de fantascope

Le Festival des cannes

Le jardin rouge-baiser

Fenêtre sur cour

La Petite Boutique des horreurs

Fantasia

Planètes

Stalker : un jardin de résilience

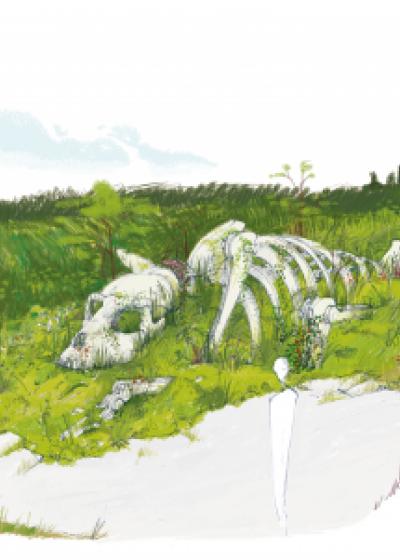

Jurassic Plantes

Les jardins de Tati

Les racines du rêve

Les cannes du Festival

Cinemazema

Nausicaä

Entre rêve et réalité

Le jardin du zapping

Le jardin de Truman

Les roseaux sauvages

Le fabuleux jardin d’Amélie Poulain

Permanent Gardens - International Garden Festival

L'habitant paysagiste

La promenade des contes enchanteurs

La serre extraordinaire

Le jardin de sous-bois

La petite serre

Permanent Gardens - Farmyard

Le paysage microcosmique